Photography by Liam Macann

Vedika Rampal

Vedika Rampal is an Indian-born emerging artist who primarily lives and practices on Darug and Guringai land in Sydney, Australia. Her post-disciplinary practice intuitively oscillates between image and image forms, using the language of sculpture, textiles, photography and text to interrogate the past to open-up the present. A recurring subtext to Rampal’s work is violence, the visible and invisible residues of Empire, that weaves itself into inherited memories, fictive imaginings and archival research. Rampal’s work reflects upon the duality of trauma and yearning, capture and resistance, loss and agency innate to these histories to suggest the simultaneity of counternarratives to imperial legacies. It is within this palimpsest of temporalities that the possibility of otherwise impossible life forms to emerge for Rampal, representative not only of endurance but of the inviolable resistance contained within residual substrates, historical artefacts and material inscriptions.

Vedika Rampal, Forms of a Fermenting Fantasy, 2023, digital print hand-transferred onto copper forms, dimensions variable. Image by Chris Mulia.

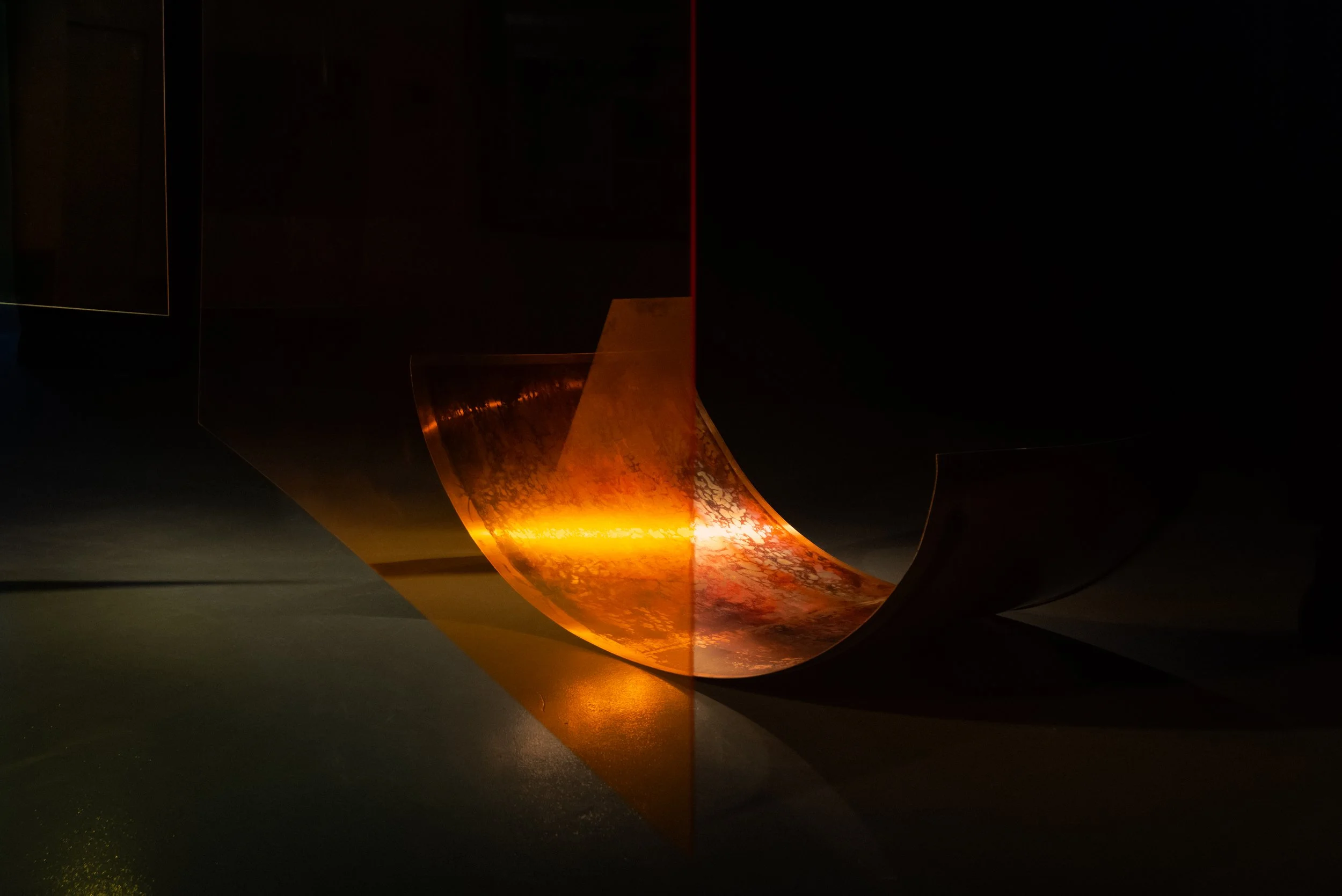

Vedika Rampal, Pilgrimage (detail), 2023, digital print hand-transferred onto three copper forms, three projections, three suspended acrylic screens, dimensions variable. Image by Liam Macann.

Tell us about your creative process. What drives your practice?

My creative process usually begins with an encounter with a site — whether that be in person or inherited through memories or the archive. So at the moment, I perceive my methodology as excavation — that word in particular I find so fascinating as its etymology reveals a slippage. Although today the verb is primarily used to reference the archeological act of removing earth by digging, its initial usage prior to the mid-nineteenth century (coinciding with the apotheosis of Empire) was used to refer to the act of forming and hollowing. It’s interesting how this shift in usage aligns with the colonial dialectic of art and artefact in which the former suggests creation and thereby is attributed to the civilised culture as opposed to the latter which is stagnant and consequently representative of the uncivilised. Collapsing this oppositional dialectic, my practice is interested in excavating colonial histories – in the dual sense of the word – to suggest the simultaneity of those processes of unearthing and forming which are imbued with a present immediacy for me.

Perhaps that is why I deliberately employ materials that hold conceptual significance and yet evade origin. After all, when researching histories and artefacts, there is an instinctual compulsion to locate lost origins. Yet a glance at the pillage, plunder and destruction of the Empire, one quickly realises how colonisation has forcefully constructed a path of linear temporality in which that past cannot be restored, contrary to the mythology of the museum which argues to have time-capsuled history, innocently behind the transparency of vitrines. As such to deny the possibility that imperial practices of preservation have been successfully able to do so without violence, I use materials that disavow origin, existing as cultural signifiers instead.

Copper is a central material in your works, as a print substrate and for sculptural outputs. What is the significance of copper in your conceptual and material practice?

Specifically, why copper? The reason is three-fold. Foremost, copper has great historical significance within Indian history, with its emergence in the pre-Harappan Chalcolithic period (2000 - 700 BCE), indexing material and technological advancement that European colonial history denied. Additionally, copper invokes early photographic history, particularly daguerreotype images from the 19th century which coincide with the emergence of the imperial shutter and the ethnographic classification of people and their objects by ethnographers and anthropologists alike.

That is, of course, the historical backdrop. More immediately, copper as a material substrate is something that profoundly contains agency for me as it overtly resists the colonial impulse to preserve. While its soft surface both recollects the violence of inscription (susceptible to all marks, fingerprints, smudges, scratches, and indents) it simultaneously endures extreme temperates and processes of heat patinas alongside being curved, guillotined and reformed.

Yet regardless, copper still resists mimetic reproduction. No matter how controlled the circulation of transferring my poor images of Ajanta onto the surface, I cannot predict where my digital photograph does and does not imprint. The image’s fragmentation indicates not only a refusal to be captured but a relinquishing of mastery and control as by remaining unfixed (I do not use wax nor varnishes on the surface), the copper too is subject to change and oxidise over time. Yet unlike other metals, copper does not weaken but it hardens. A dual allegory for colonial loss and resistance emerges.

Can you tell us more about the imagery used in your works? Where do you source these images and what stories do they share?

My recent works, Forms of a Fermenting Fantasy and Pilgrimage are in response to the Ajanta Caves (6 BCE-2CE) located in Maharashtra, India. The site was painted, carved and dwelled in by Buddhist artisans who renounced the caves during the decline of the Vakataka period and were then re-discovered by a British hunting expedition in 1819. But my encounter with them is more personal, prior to my re-learning of its history. You see, since childhood, my father had told me about Ajanta. He told me that if I wanted to understand art, at some point, I had to go there and see the celestial sculptures encapsulated within them. He had never visited the site himself.

So in January 2023, I arrived in the early morning hours with a digital camera and no tripod. Enmeshed in an undulation of thousands of local people, I was gently pushed into the opening of the first cave. Beyond the threshold, there was very little light. Once my eyes adjusted to the darkness, figures began to emerge. Left to right, right to left, ceiling to wall. All surfaces were adorned by a dense canopy of illustrations — courtesans and courtiers, kings and queens, elephants and deers, flowers and fruits, kinnaras and apsaras, bhikshus and Bodhisattvas. Hasya (mirth), karuna (pathos), rudra (anger), shringara (erotic), a complex tapestry of emotions weaved from human to animal to plant, with every being rendered as either listening to the other or looking inwardly, transcending the illusion of life in the embrace of life itself.

Until that moment, I did not know that Indian painting existed. I also did not know that the murals were so severely fragmented, not due to age or time, but due to the shellac and varnished applied to the surfaces of the caves by British and Italian conservationists in a ‘misguided attempt’ at preservation. Both these encounters, with the site and with colonial history initiated my creation of copper images/forms that reside both as subject and object somewhere in-between the sculptural and the photographic, the icon and the aniconic, likewise to the murals and sculptures of the caves themselves.

Vedika Rampal, Artefact no. ८, 2023, digital print hand transferred onto copper, 30 x 42 cm, unique copy.

Image by Chris Mulia.

Vedika Rampal, Artefact no. ७, 2023, digital print hand transferred onto copper, 30 x 42 cm, unique copy.

Image by Chris Mulia.

What is the importance of creating sites of encounter or occlusion for the audience? How does this allow you to explore processes of cultural extraction and colonialism?

In my larger installation works, I am very much interested in manipulating both colonial optics and centre/periphery relations. I am inclined toward the use of suspended coloured screens which not only frame our gaze but actively work toward filtering our vision. Yet in moving through the exhibition space, the screen can be surpassed and yet still resides somewhere within our peripheral vision. Can the colonial violence ever truly be evaded or do its residues always remind, somewhere, at the back of consciousness? I am not sure but my work asks that question regarding memory and how we perceive it in a supposedly post-colonial world. I hyphenate the word to suggest how both temporalities are inextricably linked, even after Empire, I do not think one can transcend it. Is that not the consequence?

I also negotiate the idea of access in installations. Sometimes, I install my work in such a way that a limited positionality of the viewer is enforced, restricting an all-encompassing viewpoint. At other times, while the viewer is invited into the space, moving through artefacts and screens, a vantage point is still deemed impossible. The entire site can never be viewed all at once. The experience is always contained, always fragmented. I think the question of one having the right to access another’s culture in its entirety is an important question alongside the simultaneous possibility of whether such an insight can be actualised at all? Especially when the colonial historian, ethnographer and anthropologist have previously claimed to create a totalising history “for” the uncivilised culture before.

Vedika Rampal, Pilgrimage II, 2023, digital print hand-transferred onto two copper forms, single projection, suspended acrylic screen, dimensions variable. Image by Liam Macann.

Are there any female printmakers / artists that influence you?

There are many! Pushpamala N.’s recreation of Maurice Vidal Portman’s ethnographic documentation of the Indigenous people of the Andaman Islands during the British occupation of India is one work that has deeply influenced my research. Emily Jacir’s disruption of traditional notions of the archive re-circulation of poor images, especially in her work ex libris at dOCUMENTA (13) is another example alongside Bea Schlingelhoff’s institutional critique of European museum practices as she actively dismantles any neutrality associated with the vitrine. Moreover, Kapwani Kiwanga's use of screens and Mithu Sen’s ‘linguistic anarchy’ have informed my exploration of optics and the use of text. More locally Kirtika Kain’s practice and her material construction and dismantling of hegemonic archives. All of the brilliant academics and tutors I have had throughout the course of my study. And of course, Hito Steyerl (I have mentioned the ‘originary original’ of the poor image uncountable times already!)

Finally what exciting projects are you working on at the moment?

At the moment, I have a series of image/forms going to Sydney Contemporary as an expansion of my artefact series on Ajanta from last year. I am also curating a group show of emerging artists from the South Asia diaspora heading to AIRspace Projects next month which I am very excited about. I have wanted to collaborate with this group of fellow creatives for a while now, especially with our shared yet distinct relationship with language and naming in terms of the dispossession and re-claiming of cultural narratives. There are also several unresolved threads from my honours research that I want to develop further, particularly the use of video essays and text within my work. I will be travelling at the end of the year to India to conduct further archival research at historical sites, and hopefully, in 2025 I will be travelling to the UK to study their plundered archive and reproductions of these sites.

History as a subject after all is endless — endlessly replete with ideas as it is endlessly provoking of reflection, reconsideration and re/unlearning. I am looking forward to this seemingly continual pilgrimage in and through the past, interwoven with the present.